Despite being the top recipient of China’s aid commitments in Southeast Asia, the Philippines saw only a fraction of the $30.5 billion Beijing pledged between 2015 and 2023, as political rifts, derailed projects, and maritime tensions gutted one of the region’s most hyped development partnerships.

A new report by the Sydney-based Lowy Institute reveals Beijing disbursed just $700 million over that period, leaving Manila near the bottom of the region in terms of actual aid received. The data comes amid growing concerns over the sustainability of China’s global lending model and as the Philippines reorients its foreign policy and development priorities away from Beijing.

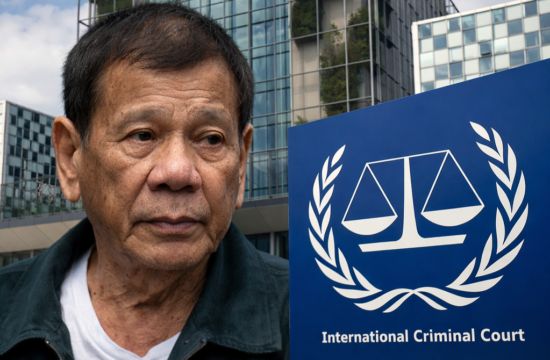

The bulk of Chinese financing commitments came during the term of former president Rodrigo Duterte (2016–2022), who pursued closer ties with Beijing under his “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure campaign. Several big-ticket deals were signed under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but most failed to break ground.

Under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who took office in 2022, Manila has slowed engagement with China and leaned more heavily into its alliance with the United States and other strategic partners. That shift coincided with the cancellation of at least three major Chinese-backed railway projects in 2023, including the proposed Mindanao Railway and two other lines connecting Laguna to Bicol and Subic to Clark.

According to the Department of Transportation, Beijing did not respond to multiple follow-up requests on financing, prompting the Department of Finance to formally pull the plug on the projects. One of the cancelled railways — the Subic-Clark connector — has since been folded into the Luzon Economic Corridor, which recently secured a $15 million commitment from the U.S. government during Marcos’ recent visit to Washington.

The only BRI-linked project to reach completion was the ₱4.5 billion Chico River Pump Irrigation Project. Beijing also donated ₱1 billion worth of defense equipment to Manila during the Duterte administration.

Of the $700 million China actually disbursed to the Philippines, 31% went to unspecified sectors, followed by 19% for transport and storage, 14% for agriculture, and smaller shares for water (12%), communications (10%), health (9%), and education (<1%).

By contrast, Indonesia — the second-largest recipient of Chinese aid in Southeast Asia — received and spent $20.3 billion of the $20.7 billion pledged by China, mostly for energy and transportation infrastructure.

The Philippines’ low absorption rate of Chinese aid reflects not just geopolitical frictions but also institutional and bureaucratic hurdles, according to Grace Stanhope, a Lowy Institute research associate who co-authored the study, in an SCMP interview.

Others believe the funding shortfall reflects deeper structural challenges.

Matteo Piasentini, a geopolitical analyst and lecturer at the University of the Philippines, said that bureaucratic coordination, domestic budget constraints, and longstanding ties with alternative donors such as Japan and the U.S. also played a role.

Chester Cabalza, president of the Manila-based International Development and Security Cooperation think tank, said the maritime standoff in the South China Sea continues to limit economic cooperation with China.

The report also comes as Southeast Asia grapples with an increasingly uncertain trade and aid landscape. Amid declining Western aid and the threat of U.S. tariffs under President Donald Trump’s policies, countries like the Philippines are walking a tightrope between strategic allegiances.

Following Marcos’ latest trip to Washington, the U.S. agreed to a modest tariff reduction on Philippine exports — from 20% to 19%. While largely symbolic, the move underscores the Philippines’ strategic tilt amid competing pressure from both superpowers.

Yet, Manila’s economy appears resilient. Despite losing out on Chinese development aid, the Philippines remains one of the top recipients of multilateral support, led by the Asian Development Bank ($16.4 billion), World Bank ($11.8 billion), and Japan ($8.9 billion), based on Lowy Institute data. China ranks a distant eighth.

Globally, China’s development finance strategy is entering a period of retrenchment. According to an earlier Lowy Institute report, in 2025 the world’s poorest countries will pay a record $22 billion in debt repayments to Beijing — marking China’s transition from major financier to dominant debt collector.

Although Beijing continues to channel funds into strategically vital partners such as Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and mineral-rich countries like Argentina and Congo, overall BRI disbursements have cratered as domestic pressures and repayment demands mount.

As China reassesses its development financing strategy, the Philippines has a clear opening to diversify its partnerships. With Beijing’s checkbook diplomacy losing steam, Manila’s best bet, according to analysts, may be to forge deeper ties with countries that share its long-term development goals.