Every August, the Philippines celebrates Buwan ng Wika, a month-long observance promoting the Filipino language and the linguistic heritage of the nation. Schools and institutions nationwide mount festivals and exhibitions honoring the power of language in shaping national identity. At the heart of the celebration is Filipino—a language based on Tagalog, designated the national language in the 20th century to foster unity in a historically diverse archipelago.

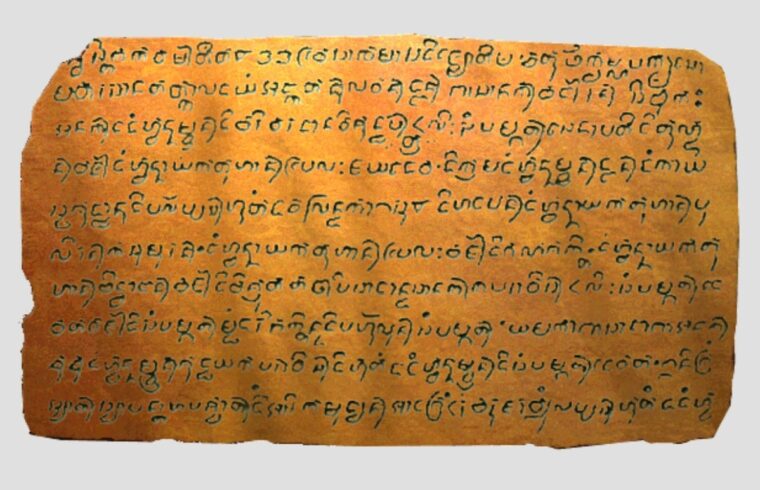

Yet behind this celebration lies an artifact that complicates the prevailing narrative of Filipino linguistic identity: the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. Dated to 900 CE, this thin, 20 by 30 centimeters sheet of blackened copper is the earliest known written document in the Philippine archipelago. Its significance extends beyond archaeology—it is a linguistic time capsule that reveals a deeply sophisticated, interconnected precolonial culture, one that communicated not through a singular native language, but through a syncretic script rooted in transregional exchange.

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription was discovered in 1987 during dredging activities in the Lumbang River in Laguna province and acquired by the National Museum of the Philippines in 1990. It remained undeciphered until Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma analyzed it and published his findings in 1992. The text, written in a script similar to the Kawi of Java, contains a legal record forgiving the descendants of a man named Namwaran from a debt of 926.4 grams of gold—a substantial amount by any standard. It also mentions a number of historical places, such as Tundun (now Tondo in Manila), Pailah (possibly in Bulacan), and Puliran (near present-day Laguna Lake), and political figures like the chief of Dewata and the lord minister of Pailah.

What makes the Laguna Copperplate Inscription particularly remarkable is its language: a complex mixture of Old Malay, Sanskrit, Old Javanese, and possibly Old Tagalog. This polyglot composition suggests not only the literacy of its scribe, but the multicultural milieu of the society that produced it. From the outset, Postma identified the primary language of the inscription as Old Malay, the maritime lingua franca of Southeast Asia at that time. He noted that several Old Malay words in the text existed in identical or closely related forms in premodern Tagalog and were also shared by Old Javanese. While Postma applied a cosmopolitan linguistic approach, he ultimately chose what he called a “Tagalog angle” to interpret the sociocultural context of the inscription. He argued that the event recorded in the text occurred within the Tagalog-speaking area of Luzon, specifically around the Manila Bay region.

This localized analysis was practical and grounded: Postma had to first verify the inscription’s authenticity—aware of past attempts to counterfeit ancient documents—before establishing its geographic relevance. Despite its use of Old Malay and Old Javanese vocabulary, Postma convincingly demonstrated that it was not an imported artifact, but rather a locally produced legal document, composed for a multilingual society already accustomed to regionwide cultural and commercial interactions.

These interpretations reinforce the idea that the Philippines was not isolated nor culturally dormant before the Spanish arrival in 1521. The Laguna Copperplate Inscription provides empirical evidence of a functioning legal and administrative system that recorded obligations and exercised authority through written agreements. The use of Kawi script—a derivative of the Pallava script of South India—also aligns the archipelago with neighboring polities such as Srivijaya in Sumatra and Medang in Java, both powerful centers of trade and Mahayana Buddhist culture during that era.

The document challenges the modern perception of a linguistically fragmented precolonial Philippines. While it is true that the archipelago was (and still is) home to a multitude of languages and dialects, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription suggests that these communities also shared access to a common elite register—a written form intelligible across various polities and ethnicities. This shared literacy implies a more unified communicative sphere at the political and mercantile level than often assumed.

This reality presents an interesting counterpoint to Buwan ng Wika. The modern national language, Filipino, was constructed during the 20th century as part of the broader nation-building project under then-President Manuel Quezon, whose birth on August 19 became the symbolic anchor of the celebration. Initially based on Tagalog, Filipino was promoted as a neutral and inclusive language. But resistance from non-Tagalog-speaking regions raised questions about its representativeness—a debate that continues today. The shift from Linggo ng Wika to Buwan ng Wika in 1997 sought to broaden the celebration to include native languages, yet Filipino remains central.

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription, in this context, offers both a reminder and a challenge. It reminds us that the Philippines has long been home to complex linguistic ecosystems shaped by mobility, trade, and diplomacy. And it challenges the singular elevation of any one language—then or now—as the exclusive vessel of national identity. Indeed, the inscription’s very existence implies that Filipinos of the 10th century were already navigating multilingual realities with sophistication and intentionality.

Moreover, the inscription complicates the narrative of Filipino as a natural linguistic evolution from Tagalog. Historically, the Tagalog script Baybayin only appears in records from the 16th century, primarily in Spanish accounts. The presence of a Kawi-based inscription in Laguna five centuries earlier suggests that the linguistic and script traditions in Luzon were far more diverse and internationally informed than previously acknowledged.

Of course, one artifact cannot stand in for an entire culture, nor does the Laguna Copperplate Inscription imply that all precolonial Filipinos wrote or spoke in Old Malay or Sanskrit. It was likely an elite language used in official transactions, much like Latin in medieval Europe. But its presence is indisputable. And in a country still debating the boundaries of its linguistic identity, that alone is significant.

In reexamining Buwan ng Wika through the lens of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, we are offered an opportunity to deepen our understanding of what it means to be Filipino—not by narrowing our view to a single language or narrative, but by embracing the multilingual, multi-script, and multicultural realities that have always existed across the islands. It reminds us that linguistic identity in the Philippines was never singular, never static. The earliest written record of our archipelago is neither entirely native nor foreign—it is both. It speaks of debt and forgiveness, of rulers and regions, but also of intercultural fluency, centuries before the Philippines became a republic.