When China’s Chang’e-6 spacecraft made history last year by retrieving the first lunar samples from the Moon’s far side, it was widely celebrated as a technical milestone and a geopolitical statement of Beijing’s growing space ambitions.

Yet buried in a recent paper by Chinese engineers is a striking detail: the Philippines, a much smaller power locked in maritime disputes with Beijing, quietly forced China to alter the mission’s flight path.

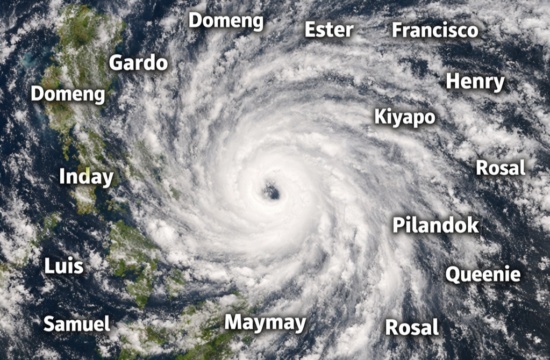

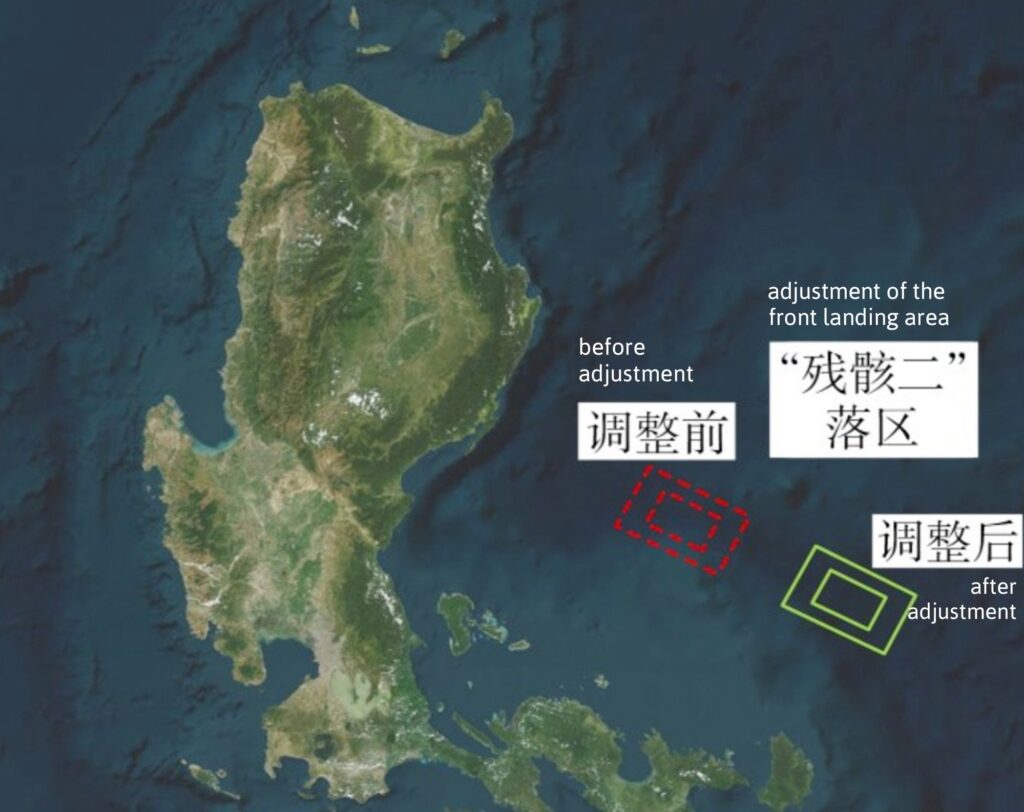

According to the study, published in China’s Journal of Astronautics, the Long March-5 rocket that carried Chang’e-6 into orbit in May 2024 was programmed to jettison its nose cone several dozen seconds later than initially planned. That small adjustment pushed falling debris farther into the Philippine Sea, away from Luzon’s eastern coast.

An accompanying diagram in the paper showed the original debris zone directly off Luzon, the Philippines’ largest and most populous island, before the timing shift nudged it out to sea.

“In response to new domestic regulations and evolving claims over foreign territorial sea baselines, we fine-tuned the launch trajectory timing,” wrote Wang Qiong, the mission’s deputy chief designer, and his colleagues. Without naming the Philippines, the authors acknowledged the change was made to avoid “sensitive maritime areas.”

For Manila, the gesture carried more weight than the few seconds of delay might suggest. The Philippines has long objected to falling Chinese rocket debris, with fragments from Long March-5B boosters washing up on Palawan and Mindoro in 2022 during China’s Tiangong space station construction. Earlier this month, more debris from a Long March-12 rocket carrying internet satellites landed near a Philippine island, prompting officials to condemn the risks posed to people, ships, and aircraft. By pressing Beijing to steer clear of its waters during the Chang’e-6 mission, the Philippines effectively imposed its will on the trajectory of a superpower’s lunar program—an unusual reversal of the regional dynamic in which China typically dictates terms.

The Chang’e-6 mission itself was a feat of engineering improvisation. Originally built as a backup to the Chang’e-5 probe that collected near-side samples in 2020, the spacecraft was reconfigured for the more ambitious challenge of landing on the Moon’s hidden hemisphere. Its journey, launched from Hainan Island on May 3, 2024, required a retrograde orbit against the Moon’s spin that stretched the voyage from the usual 23 days to 53. The lander touched down on June 1 in the Apollo Basin, part of the vast South Pole–Aitken impact region, collected nearly two kilograms of rock and soil, then docked with an orbiter for the return flight to Inner Mongolia, where the capsule landed by parachute on June 25.

Chinese engineers later revealed that the mission required another delicate adjustment on its way home. The spacecraft’s original re-entry path would have skimmed the airspace of an unnamed West Asian country. To avoid diplomatic friction, they fine-tuned the re-entry angle by just two-tenths of a degree, a minuscule tweak that ensured a clean descent without crossing restricted skies.

The samples retrieved are now under analysis in China, with portions expected to be shared with international partners. The mission marked the first time material was retrieved from the Moon’s far side and required trajectory changes both at launch and re-entry to avoid sensitive maritime and airspace zones, reflecting how technical planning in space exploration can intersect with terrestrial boundaries.