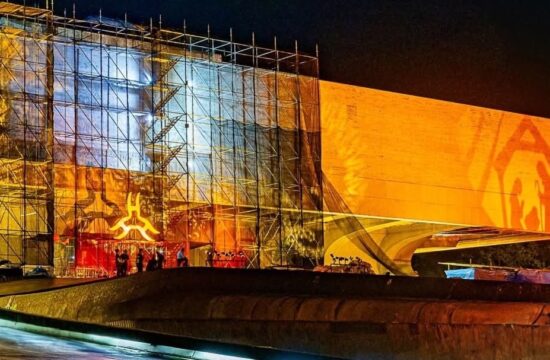

At the grand stone façade of the Manila Cathedral, a figure carved from travertine looks serenely upon the faithful. She is St. Rose of Lima, honored across the Americas as a beloved saint, canonized in the 17th century, and quietly remembered in the Philippines as its secondary patroness.

“Her presence at the cathedral reminds faithful and pilgrims to bear witness to purity, graceful life, and hope as we continue our pilgrim journey on this earth,” the cathedral noted in a post on Saturday, August 23, marking her feast.

Born Isabel Flores de Oliva in Lima, Peru, on April 20, 1586, she was the daughter of a Puerto Rican soldier and a mother of Spanish descent in the bustling colonial outpost of the Spanish Empire. According to legend, a servant once saw her infant face glow and transform into the likeness of a rose—a vision that gave her the name she would carry for life.

From her earliest years, Rose embraced austerity and prayer. She grew up sewing fine embroidery, cultivating flowers to support her household, and tending to the poor and sick with quiet devotion. Though her parents urged marriage and resisted her desire to enter a convent, she carved out a space for holiness at home, joining the Third Order of St. Dominic at 20 and turning a backyard hut into a hermitage for prayer and penance. She lived simply, prayed intensely, and died young, passing away in Lima on August 24, 1617, at just 31.

Her sanctity drew swift recognition. Less than 50 years after her death, Pope Clement IX declared her “blessed” in 1667, and Pope Clement X canonized her in 1671, making her the first Catholic saint born in the Americas. But Rose’s significance reached far beyond her native Peru. In the papal bull Sacrosancti Apostolatus Cura, Clement X named her not only the principal patroness of Peru and of the Americas but also of the Philippines and the Indies, binding together lands scattered across oceans through her spiritual guardianship.

That transoceanic connection was not incidental. Manila, then the easternmost outpost of Spain’s empire, was tied to Lima and Mexico through the galleon trade, a vast network that carried silver, silk, and saints across the Pacific. The devotion to St. Rose, carried by missionaries and colonists, took root in the archipelago alongside other imported devotions, weaving her into the fabric of Philippine Catholic life. For centuries, her feast was observed on August 30, in line with Rome’s calendar, before the liturgical reforms of 1969 shifted it to August 23. In Peru, however, the older date remains a national holiday.

In the Philippines, her patronage once stood alongside that of St. Pudentiana, another early co-patroness. Both saints, however, were reclassified in 1942 by Pope Pius XII as secondary patrons, their place in national devotion eclipsed by the Immaculate Conception, who was declared the principal patroness of the country. Yet traces of St. Rose’s legacy endure. Whole towns, most famously Santa Rosa in Laguna, still bear her name, while parish churches dedicated to her can be found from Pasig and Rizal to Albay and Cebu. Her likeness appears not only in Manila’s cathedral but also in countless parish altars, often crowned with roses, a symbol of her purity and penance.

Her story, even in its austerity, carries a paradoxical grace. The young woman who wore a crown of thorns beneath a garland of roses, who mortified her body while tending to the hungry and sick, became an emblem not of denial alone but of hope.

She was remembered, the Catholic Church recounts, with miracles at her death: the air in Lima perfumed with roses, petals said to have fallen from the sky. The image endured, spreading through the Americas, the Indies, and the Philippines, reminding distant peoples of the beauty and sacrifice entwined in a single life.

To recall St. Rose today is to recall more than a saint. It is to remember how faith once linked two continents, how Manila and Lima, bound by ships and empire, also shared patrons and devotions.

Her statue at the Manila Cathedral is not merely an ornament of stone but a sign of a forgotten chapter of Philippine Catholic identity, a reminder that the nation once claimed a Peruvian woman as its own protector.

In honoring her, the Philippines reclaims a fragment of its history—a history in which faith, commerce, and empire intersected, and where purity and hope, embodied by a saint crowned in roses, could span the distance of oceans.