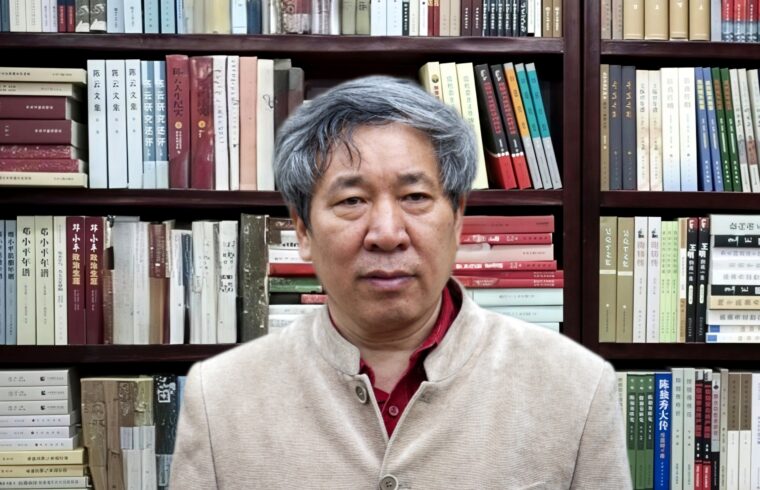

Yan Lianke, one of China’s most acclaimed yet controversial novelists, says his idea of literary freedom depends on discipline, not defiance. “Freedom in writing, discipline in publishing,” he says — a phrase that reflects both artistic conviction and survival.

At 67, Yan appears unfazed by the speculation surrounding him as a Nobel Prize contender. “Any pressures I face now stem from within my own existence and from literature itself,” he told the South China Morning Post in a recent interview.

His novels — Dream of Ding Village, Lenin’s Kisses, The Four Books — are feverish allegories of rural China, where the absurd and the tragic blur into something almost mythical. They have earned him the Franz Kafka Prize and the Lu Xun Literary Award, and, more controversially, the reputation of being one of China’s most frequently “banned” authors.

But Yan rejects the label. “Please do not call me a banned author,” he says. “I am simply an ordinary novelist.” His defiance is quiet, almost grateful. “Without tolerance, understanding, and protection,” he adds, “my writing would not have endured to this day.”

Censorship, for Yan, is not the greatest barrier to literature. “The most formidable challenge,” he explains, “is the innate habit of self-censorship cultivated from childhood.” What outsiders call censorship, he prefers to view as “publishing discipline” — a social mechanism, not a moral judgment. “When a social system encounters literature,” he says, “it inevitably takes a stance and makes choices. It stems from the nature of the system itself.”

Rather than resist that structure, Yan navigates within it. He sees no contradiction between freedom and limitation — only the tension that produces art. “To a greater or lesser extent, its literary tolerance permits a writer to write freely,” he says. What he sacrifices in publication and fame, he gains in creative clarity. “In artistic creation, I have become a literary anarchist.”

Anarchism, in his sense, is not disorder but autonomy — the refusal to write by decree or fear. His principle is simple: “Any human experience is fair game for literature.” Whether confronting the Great Famine or the Cultural Revolution, he chooses subjects that wound him personally. “If I write about it,” he says, “it must pierce me.”

Yan’s years as a People’s Liberation Army soldier shaped this outlook. He began writing during his 26 years in the military, a period he calls “the most significant chapter of my life.” It was also the time when China shifted from isolation to openness. “Without those years,” he says, “I would not be who I am today.”

Ironically, it was the military that offered him protection. After his 1991 novel Summer Sunset was banned, he wrote six months of self-criticisms but remained a “professional army writer.” When Dream of Ding Village faced restrictions, his employer relayed a message from authorities: “You must take good care of Yan Lianke; he is a talented writer. We are only banning him because it is our job.” The memory still moves him. “China is not what you imagine it to be,” he says. “At least, not entirely.”

Yan’s view of Chinese literature abroad is equally clear-eyed. Despite government efforts to “tell China’s stories,” he sees limited global impact. “If you visit bookshops in Europe or America,” he observes, “you’ll find only a handful of Chinese writers on the shelves.”

Asian literature, he believes, has yet to form a coherent identity comparable to Latin American or European traditions. “We can see the outlines of Japanese, Korean, and Chinese literature,” he says, “but we cannot yet define East Asian literature.” The idea of a shared literary sphere, once proposed by Haruki Murakami, remains, in Yan’s view, a noble but unrealized dream. “For Asian literature to have a true global presence,” he says, “it must produce works that influence writers across languages — not just appear on bookshelves.”

Despite the rise of artificial intelligence and digital writing, Yan remains rooted in older habits. He still writes every manuscript by hand. “The abyss of death now stretches before me,” he admits. “Thus, my only concern is what I want to write before I die.”

The questions that preoccupy him are not political but existential. “A banned book is not necessarily a good book,” he says. “Everything must return to the fundamentals of art.” His concern is not whether Chinese literature is global enough, but whether writers anywhere still dare to think differently. “Our tragedy,” he says, “is that we remain trapped in 19th-century realist thinking.”

If Yan sounds like a dissident, he is not. His rebellion is interior. He resists formula, not authority; conformity, not country. The paradox of his career — condemned yet protected, restricted yet free — embodies what he calls “the wondrous possibility inherent in literary censorship and tolerance.”

To read Yan Lianke today is to encounter a writer at peace with contradiction — a man who finds clarity not in defiance but in the delicate calibration between freedom and restraint. His vision of literary anarchy is not one of destruction, but of persistence: the courage to write what must be written, and the discipline to live with the consequences.