Across China’s fast-moving consumer landscape, joy has become a serious business. Born from the fandoms of anime, comics, and gaming (ACG), the so-called “guzi” economy now turns emotional spending into a thriving cultural industry.

Derived from the English “goods,” guzi refers to a vast array of spin-off merchandise tied to popular intellectual properties: blind-box toys, trading cards, acrylic badges, plush dolls, and novelty stationery.

For China’s Gen Z and young millennials, these items aren’t mere trinkets; they are tangible expressions of happiness, belonging, and self-identity. “Buy goods for good moods,” as the saying goes, has become the quiet mantra of a generation that consumes for emotional connection rather than utility.

The numbers are striking. According to iiMedia Research, China’s guzi market reached 168.9 billion yuan (US$23.5 billion) in 2024, marking a 40.6% year-on-year increase, and is projected to surpass 300 billion yuan by 2029. It moves in tandem with the country’s broader ACG economy, which was valued at 597.7 billion yuan last year and is forecast to hit 834.4 billion yuan by 2029. Beneath the fun and fluff lies a profound cultural shift—one that redefines “Made in China” as “Created in China.”

This rise of the guzi economy is more than a shopping trend; it’s a social movement powered by digital natives who equate consumption with emotional wellness.

“Today’s youth, who are growing up in materially abundant environments, view consumption more as a form of expression and participation. The guzi economy cares more about personal aesthetics, cultural identity, and community belonging, which makes it a great success,” observed Lyu Mei, head of strategic consulting at JLL East China.

What used to be a niche hobby has become a lifestyle, blurring the boundaries between retail, art, and pop psychology.

For brands like Pop Mart and Kayou, the guzi boom represents a creative revolution. Pop Mart, the Chinese trend-toy giant, reported 13.88 billion yuan in revenue in the first half of 2025—a 204.4% year-on-year surge. Its founder, Wang Ning, was recently named by Forbes as China’s 10th richest person, credited with turning miniature toys into a billion-yuan business model. Meanwhile, trading card maker Kayou, with licenses from Ultraman to My Little Pony, posted 10.06 billion yuan in 2024 revenue, up 277.8% from the previous year, with profits soaring 378%.

Kayou vice president Lu Dazhen explained that when a country’s per capita GDP reaches around US$10,000, cultural industries tend to flourish, as consumers begin seeking emotional and lifestyle fulfillment beyond material needs.

The emotional value behind these products is what keeps the industry resilient and expanding. Visiting a guzi store on weekends has become a form of therapy. For young buyers, blind-box toys, trading cards, or plush collectibles offer a quick dopamine hit—a dose of comfort amid the pressures of urban life.

“These days, people are not just buying stuff because it’s useful; they’re looking for things that make them feel good,” said Liu Xiaobin, chief marketing officer of Miniso. “Trendy guzi toys and collectibles give young people a quick mood boost and a break from everyday stress. Guzi-related communities also help them connect with others.”

At the center of this feel-good phenomenon is one mischievous creature: Labubu. With its pointy ears, jagged teeth, and wild tuft of hair, Labubu is instantly recognizable—a blend of menace and cuteness that somehow feels both nostalgic and new. Created by Hong Kong artist Kasing Lung in 2015 as part of his picture book series The Monsters, Labubu was initially conceived as a side character inspired by Nordic fairy tales and the artist’s fascination with The Smurfs. That idea gave birth to an unlikely global icon.

A decade later, Labubu has become the face of the guzi economy, leading the charge from obscure art figure to global collectible. Each Pop Mart release sells out within minutes; limited editions are flipped for multiples of their retail price on resale platforms. In June 2025, a mint-green Labubu figure fetched 1.08 million yuan (US$150,540) at auction, cementing its status as both cultural artifact and financial investment. Its charm lies in imperfection—a playful, “ugly-cute” aesthetic that resonates with a generation raised on irony, authenticity, and internet humor.

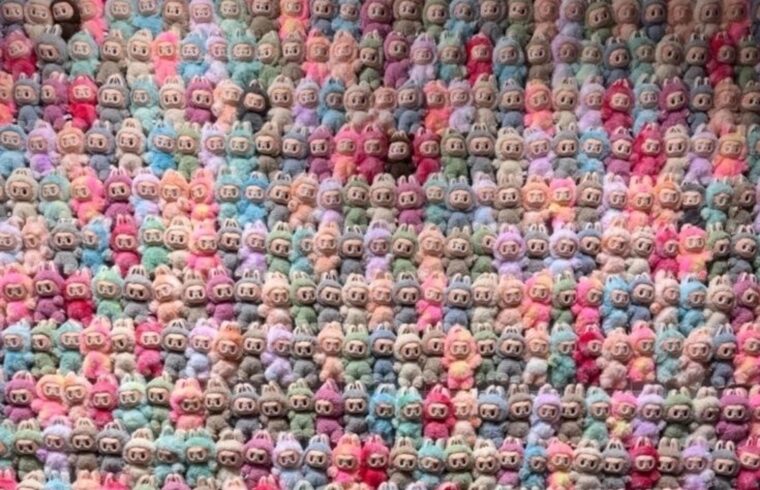

This year, Labubu and its companions in The Monsters universe are celebrating their 10th anniversary with a landmark exhibition in Shanghai titled “Monsters by Monsters: Now and Then,” running until November 8, 2025. The show is a collaboration between Pop Mart and How2Work, bringing to life a decade of whimsy and imagination. Visitors enter through a tunnel of more than 1,100 Labubu plush dolls, an immersive and hypnotic installation that turns nostalgia into spectacle. Nearly 300 original manuscripts and sketches by Lung are displayed, charting the evolution of The Monsters from storybook characters into global design icons.

“When I was young, I used to read many comic books, including The Smurfs,” Lung explained. “In my mind, a Smurf is a monster, but it’s a very cute monster. And there’s the reason I created Labubu, because I’ve had many inspirations from when I was young, and many inspirations from The Smurfs.” His words echo throughout the exhibit, which feels less like a retrospective and more like a portal into childhood imagination.

The celebration has drawn international attention. Apple CEO Tim Cook visited the Shanghai exhibition and met with Lung and Pop Mart’s Wang Ning, later sharing, “Kasing’s imagination and art have brought joy to so many people.” The event forms part of a global anniversary tour that began with Lung’s collaboration with French luxury house Moynat on a Labubu-themed capsule of bags, charms, and travel accessories—an emblem of how designer toys and high fashion are now intersecting in the “joy economy.”

Labubu’s success story mirrors China’s creative rebranding. Once known primarily for mass production, the country is now exporting imagination. The guzi movement has reshaped global perceptions of “Made in China,” presenting it instead as a symbol of playfulness, individuality, and emotional sophistication. What might appear trivial—tiny toys, trading cards, collectible charms—is in fact a trillion-yuan industry powered by creativity and cultural confidence.

At its core, the guzi phenomenon reveals a profound truth about modern consumption: people are not just buying products, they are buying stories, feelings, and fleeting moments of connection. It’s retail therapy reimagined as art, identity, and community. As The Monsters celebrate a decade of joy, the grin of Labubu—equal parts naughty and endearing—captures the mood of a generation learning that happiness, too, can be designed, packaged, and shared.