Most people discover their culture through school lessons, family keepsakes, or childhood rituals. Robert Lane found his by choice, devoting his life in the Philippines to a decades-long mission to document and protect a heritage not originally his own.

At 89, Lane remains an arresting presence—tall, fair, and neatly dressed as he moves through a room of antiques with the ease of someone who has spent a lifetime listening to what objects reveal. As founder of the Silahis Arts & Artifacts Center in Intramuros, he has become one of the country’s most steadfast advocates for preserving Filipino craftsmanship, even if he rarely describes himself that way.

His connection to the Philippines began unexpectedly. After teaching at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand, he arrived in Manila and felt an instant pull. “Well, I came from Thailand… But I came here and I liked it,” he told Asia Society Philippines. The reason he stayed, he added, was simple: “Well, the people are friendly.” Over time, that sense of welcome deepened into a sense of belonging. “Well, I became more Filipino,” he said—an intimate acknowledgment of a life shaped not by ancestry but by immersion.

Lane initially taught in the country—philosophy and theology at Ateneo de Manila University, then history at De La Salle University—but his passion for material culture soon took over. It was an extension of an earlier chapter in his life, when he worked with Native American communities and learned to recognize value in objects embedded with memory. That instinct sharpened when he settled in the Philippines, where every region carries its own visual vocabulary of craft, ritual, and everyday utility.

Those who worked closely with him often noted the depth of his knowledge. In an interview by Asia Society Philippines, Athem Fabula, who has been with Silahis Center for 40 years, said Lane understood certain aspects of Philippine history “better than some natural Filipinos,” and that his influence reshaped her appreciation for local crafts. She said she began noticing details she once overlooked—textures, meanings, stories—because Lane taught her to look again.

For Lane, preservation is more than collecting. It is the act of paying attention before memory slips and meaning fades. He has always believed that heritage survives when people understand why it matters, and that the smallest object can hold a nation’s sensibilities if people choose to see it.

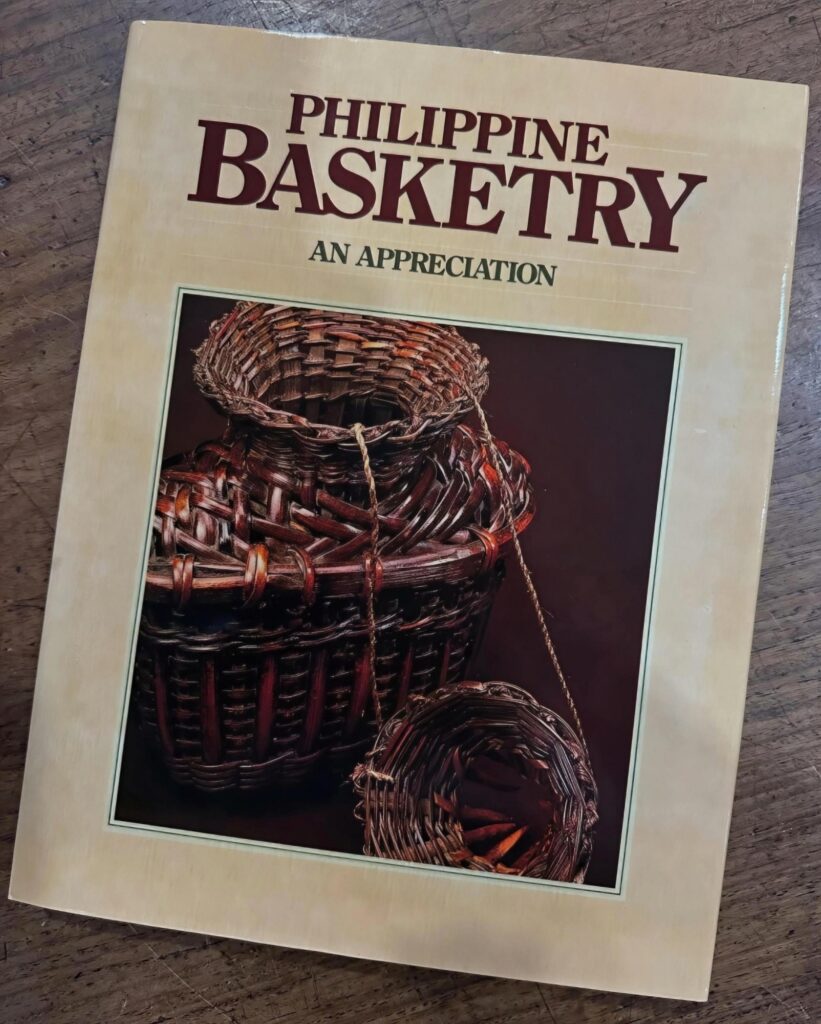

His most enduring documentation is Philippine Basketry: An Appreciation, published in 1986. Lane spent a year traveling through remote towns to study how baskets were woven into the logic of daily life—carriers for harvests, tools for fishing, vessels for rituals. He chose basketry because he saw it as a universal beginning. It was, he said in the interview, “the first art form that people made before pottery,” a reminder that innovation is often born from the simplest needs.

Lane’s authority as an appraiser also grew, leading government offices, collectors, and institutions—locally and abroad—to seek his guidance. Yet he never appeared intoxicated by recognition. When asked what achievements he was most proud of, he downplayed his legacy, saying he had “not achieved much,” a remark that contrasted with the decades he spent safeguarding cultural memory.

He admired the Filipino capacity to reimagine the everyday—resourcefulness shaped not by abundance but by adaptation. His favored example was the egg basket: cone-shaped so eggs rest firmly without rolling. To him, it was a perfect illustration of the Filipino instinct to design with both purpose and imagination. He held similar admiration for painters like Fernando Amorsolo, whose scenes of rural life he believed captured something essential about the nation.

Silahis Center, the physical heart of Lane’s work, began modestly from his porcelain collection and eventually grew into a six-level cultural landmark. It brought together antique galleries, artisanal shops, books, and regional crafts under one roof. The pandemic forced it to scale down, but its mission remained intact—representing islands across the archipelago, much like the seven rays of its logo. Lane ensured its spirit aligned with its name: Silahis, meaning “new beginning,” a place where heritage is not archived but encountered.

What started as a childhood habit of collecting teddy bears became a lifetime devoted to honoring Filipino artistry. Lane’s story is not the typical narrative of roots or ancestry; it is something rarer—a deliberate choice to adopt a culture and defend it with steadfast affection.

His message has always been clear: culture endures when people care enough to see it, preserve it, and pass it on.

Follow PHILIPPINES TODAY on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for the latest updates.