December 30 marks the martyrdom of José Rizal, a date often remembered through wreath-laying and recitations of his novels. Yet beyond the pen and the martyrdom lies another Rizal—one who measured land, drafted elevations, and imagined education with the precision of numbers and lines.

Long before he became the nation’s moral compass, Rizal trained his eye and mind as a geodetic engineer, mastering the discipline of measurement at a time when land meant power, livelihood, and justice. This lesser-known facet of his life reveals not a contradiction to his humanism, but its structural foundation: Rizal understood that ideas needed form, and reform required systems grounded in accuracy.

Rizal enrolled at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in 1877 to study agrimensor y perito tasador—land surveying and property assessment. He passed the licensure examination that same year, an extraordinary feat for someone barely 17, though colonial regulations forced him to wait until November 1881 to receive his license. In doing so, he became the first Filipino licensed geodetic engineer, and certainly its youngest. The training was exacting. Surveying demanded mathematical rigor, patience in the field, and a disciplined sense of proportion—skills that would later surface in both his writing and civic projects.

The profession was not abstract for Rizal. He grew up in Calamba, where land ownership and boundaries shaped everyday life under friar estates. As a surveyor, he learned to mark property limits and compute land areas, tools crucial in disputes between tenants and powerful landlords. Measurement, for Rizal, was never neutral; it was a way of asserting truth against abuse. It is no coincidence that today he is regarded as the patron and role model of the country’s geodetic engineers, a profession that stands at the intersection of science, law, and social equity.

Rizal carried this practical intelligence into exile. In Dapitan, he planned and marked streets, applying surveying principles to organize space for a small community. Even in confinement, he thought like a builder of towns—orderly, humane, and forward-looking. The same mindset guided his most ambitious unrealized project: a modern academy.

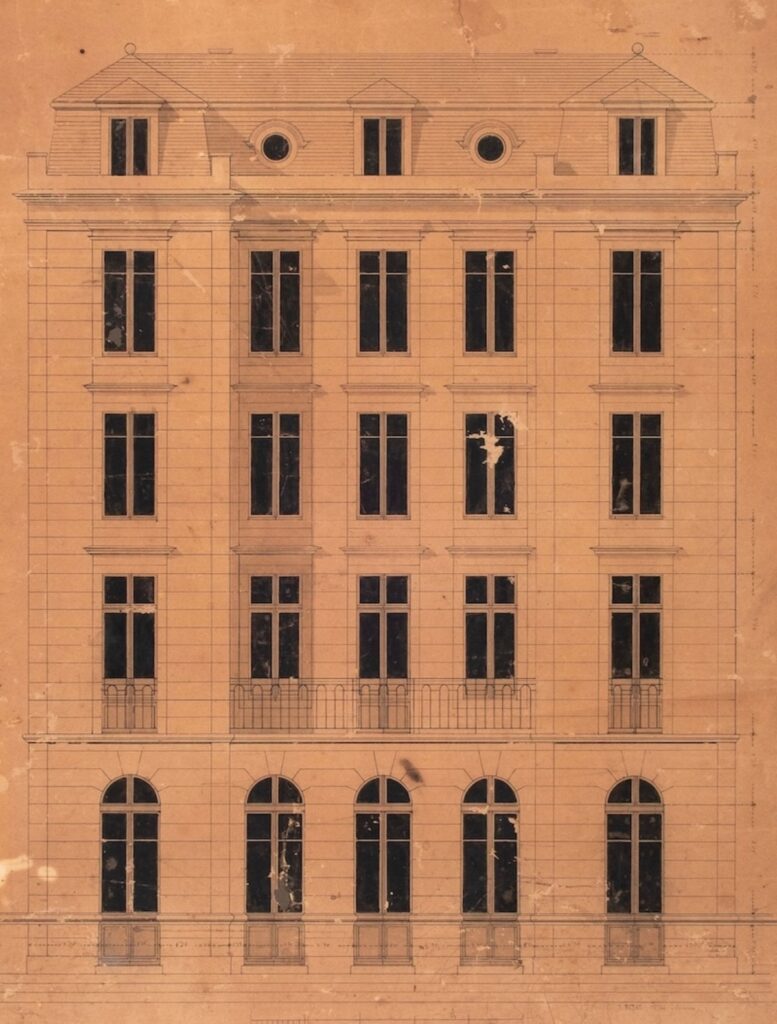

During his stay in Hong Kong from 1891 to 1892, Rizal envisioned a school that balanced intellectual rigor with physical development. Education, in his view, required movement, discipline, and competition—three-hour walks, examinations for prospective teachers, and a curriculum that trained both mind and body. Unlike many reformers who stopped at ideas, Rizal drafted an actual architectural plan for this academy, complete with numerical measurements. The surviving elevation of the façade, signed and dated March 1892, shows a mind comfortable translating ideals into built form.

Architectural historian Gerard Lico situates this drawing firmly within late 19th-century European architectural discourse. In his notes, Lico explains that the meticulously rendered façade exemplifies French Second Empire and Beaux-Arts classicism encountered by Rizal during his European sojourn.

Organized into five symmetrical bays, the composition rises from a plinth with tall arched windows at the piano terreno, ascends to a piano nobile defined by rectangular French windows and wrought-iron balconettes, and culminates in a mansard roof with dormers and central oculi.

According to Lico, the disciplined rhythm, proportional precision, and restraint of ornament reflect Rizal’s assimilation of Catalan academic classicism, Parisian boulevard architecture, and German technical drafting—evidence of a polymath translating architectural order into a vision for modern education.

Rizal’s intellectual circles in Europe further shaped this vision. Among his close associates was German scholar Adolf Bastian, an advocate of the “unity of mankind” who would later found the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. Rizal shared this belief in common humanity, contributing Philippine ethnographic artifacts to the museum’s collection—objects that have since been catalogued and documented by the National Museum of the Philippines. These exchanges placed Rizal within a progressive European network that valued culture, science, and education as instruments of social advancement.

That same milieu likely introduced him to the Lette Verein in Berlin, a pioneering institution dedicated to equipping women with vocational skills such as photography and typesetting. The resonance is striking: the Lette Verein’s building, which still stands today, bears a strong resemblance to Rizal’s academy drawing. The connection gains weight when one recalls that Noli Me Tangere was printed in Berlin by a press associated with the Lette Verein’s typography school—an early convergence of education, technology, and emancipation.

Seen through this lens, Rizal’s advocacy for education, including his encouragement of women to pursue learning, acquires spatial and technical depth. He did not only argue for schools; he imagined how they should be built, measured, and organized. His geodetic training grounded his reformist zeal in the realities of land, structure, and systems.

To remember Rizal on December 30 is to honor more than a writer or a martyr. It is to recognize a professional who understood that nationhood requires accurate lines as much as lofty words. In measuring land, drafting façades, and planning towns, Rizal surveyed the future—one carefully plotted coordinate at a time.

Stay updated—follow Philippines Today on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for more stories.