Germany’s security debate is no longer confined to European borders, but it is still searching for a language equal to its widening reach. At a recent forum in Manila, the conversation suggested that Berlin’s evolving posture in the Indo-Pacific is less about dramatic shifts than about quiet recalibration—one that is careful in tone, yet consequential in effect.

The discussion, convened by Asia Society Philippines, unfolded around a shared recognition that the international system is under strain. Georgi Engelbrecht, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group, described the moment as one that is “liberal, nor very international, nor very orderly.”

The remark was not a lament so much as a starting point. “And if we accept that as a frame, what does it then mean for us as Germans, as Filipinos, and so forth. Now, I was given the topic of the NATO, which was very interesting, because as most of you know, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was founded at the time of the Cold War, with a very defined and clear mandate.”

That mandate, Engelbrecht implied, has not disappeared but has become less geographically contained. Security developments now move easily between regions. “What happens in Europe is just as important to Pacific countries as what is happening and vice versa: when Putin lets North Korean soldiers fight against Ukraine, that has a direct impact on Europe’s security. Any unchecked rivalry between major parties has to be of concern to us, for it affects our global interests and is to our detriment,” he said.

Seen from Southeast Asia, this interdependence carries both reassurance and ambiguity. Germany’s growing engagement in the Indo-Pacific reflects an understanding that stability in the region underwrites global prosperity, including Europe’s own. Yet, as Engelbrecht has argued in recent analysis for The Diplomat, the region is also marked by uneven capacity and unresolved internal constraints.

In the Philippines, for example, ambitious defense modernization plans coexist with procurement delays, budget pressures, and institutional bottlenecks, creating a gap between strategic intent and operational reality. External partners, Engelbrecht has noted, are often drawn into this gap—valued for their support, but also constrained by local limits they cannot easily overcome.

This tension helps explain why NATO’s gradual outreach to the Indo-Pacific prompts mixed reactions. An alliance rooted in the Euro-Atlantic is edging toward wider partnerships with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, guided by an updated strategic concept and individually tailored partnership programs. To some, this signals adaptation to a globalized security environment; to others, it raises concerns about dilution of focus and overstretch, particularly as Europe confronts its most serious military crisis in decades.

Germany’s Indo-Pacific Policy Guidelines, introduced in 2020, attempt to manage this complexity through breadth rather than confrontation. They emphasize multilateralism, climate action, peace and security, human rights and the rule of law, fair and sustainable trade, digital connectivity, and people-to-people exchange.

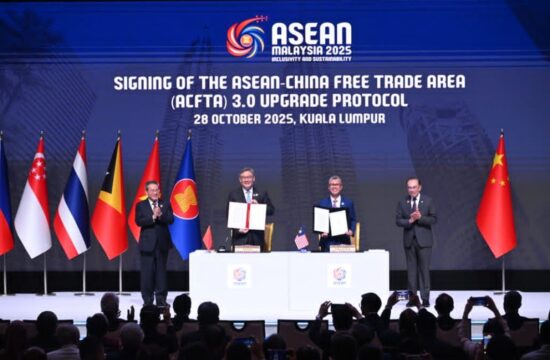

Five years on, these guidelines have been reinforced by clearer political commitment under the Merz government, more frequent high-level visits, expanded military exercises and deeper defense cooperation, including a Germany–Philippines agreement concluded in mid-May 2025. The approach embeds security engagement within a wider diplomatic and economic framework, signaling continuity rather than rupture.

Still, Engelbrecht’s broader work suggests that such frameworks will be tested less by their language than by their follow-through. As regional states hedge amid sharpening U.S.-China rivalry, middle powers like Germany face pressure to translate principles into predictable behavior. In Southeast Asia, where strategic autonomy is prized, consistency often matters more than scale.

The question, then, is not whether Germany is present in the Indo-Pacific, but how it chooses to be present. Proposals for coordinated maritime activities, participation in security and economic minilaterals, and denser regional dialogues point toward what Engelbrecht described as multi-level diplomacy. They are calibrated measures, designed to signal resolve without provocation, and partnership without alignment against any single actor.

The Manila forum, titled “Eyes on Germany: Navigating Security in a Changing World,” ultimately reflected a distinctly German dilemma. In an era of strategic flux, doing too little risks irrelevance; doing too much risks overreach. Berlin’s challenge in the Indo-Pacific is to make its engagement visible enough to matter, yet measured enough to endure.

Follow PHILIPPINES TODAY on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for the latest updates.