As the Philippines prepares to take the helm of ASEAN, the question facing Southeast Asia is not whether the bloc matters—last year proved it still does—but whether it can hold its line on neutrality at a moment when great power rivalry is pressing harder than ever.

For Manila, the challenge is sharper: how to lead a consensus-driven organization while pursuing one of the region’s most assertive positions in the South China Sea.

The timing is unforgiving. ASEAN enters the Philippine chairship having raised its global profile under Malaysia, capped by the admission of Timor-Leste and a widened network of partnerships across both the Global South and Global North. Yet beneath that momentum lie fractures that test the bloc’s core promise of unity. Myanmar’s civil war remains unresolved, social unrest continues to expose inequality across member states, and the fragile Thailand–Cambodia ceasefire is already showing strain—a reminder that old disputes can still ignite with little warning.

These regional stresses have unfolded against an unsettled global backdrop. U.S. President Donald Trump’s brief, transactional foray into Southeast Asia last year underscored Washington’s growing discomfort with multilateralism, even as it struck selective trade and security deals. His decision to skip the main APEC leaders’ meeting in South Korea spoke louder than any communiqué. Many in the region now question not just American reliability, but whether U.S. engagement still comes with a long-term commitment to regional stability.

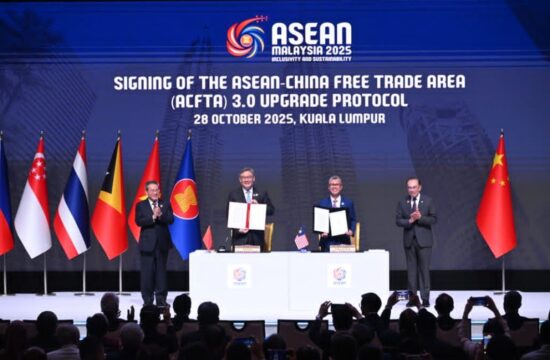

China, by contrast, has moved with patience and purpose. From upgrading its free trade agreement with ASEAN to reaffirming the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), Beijing has framed itself as a steady partner for open trade and institutional continuity. This does not erase anxieties over Chinese power, particularly in maritime Southeast Asia, but it has sharpened the strategic dilemma for ASEAN: how to engage China deeply without sliding into dependence, and how to manage the U.S. without becoming an arena for rivalry.

That balancing act—strategic neutrality—has long been ASEAN’s defining strength. It was on display in Kuala Lumpur, where Malaysia pressed ahead with engagement despite domestic protests and intense external pressure. The message was clear: ASEAN talks to everyone, aligns with no one, and keeps its own house together through dialogue rather than coercion.

This is the principle Manila inherits—and the one it risks testing most. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s more forward-leaning South China Sea policy reflects real pressures at home and genuine security concerns. But it also diverges from the cautious diplomacy preferred by several ASEAN partners, who fear being drawn into a contest they neither control nor benefit from. If that gap widens, ASEAN’s credibility as a neutral convener could suffer, just as regional disputes demand more, not less, collective stewardship.

The renewed tensions between Thailand and Cambodia sharpen the stakes. Analysts are right to warn that the dispute is not merely bilateral but a measure of ASEAN’s capacity to manage conflict among its own members. The consensus among regional experts is striking: durable solutions are more likely to come from ASEAN-led mechanisms than from outside mediation, however dramatic the latter may appear. Continuity, not headline diplomacy, is what stabilizes fragile ceasefires.

For the Philippines, this means an already crowded agenda will grow heavier. Manila has signaled it will prioritize the South China Sea and Myanmar, both legitimate and urgent concerns. But leadership of ASEAN is not about advancing national priorities alone; it is about sustaining a collective process that often moves slower than any single capital would like. A coordinated transition—with Malaysia continuing technical stewardship while Manila provides political momentum—could help preserve credibility and prevent disputes from slipping through the cracks.

Ultimately, ASEAN’s relevance lies in what it offers a fractured world: a forum that still believes in engagement over exclusion, rules over raw power, and dialogue over diktat. As Washington turns inward and Beijing presses outward, that middle ground is narrowing—but it is not gone. Whether it holds may depend on Manila’s ability to separate firmness from partisanship, and leadership from alignment.

For the Philippines, the task is less about choosing sides than about keeping space open—for diplomacy, for trade, and for ASEAN itself. If Manila can do that, it will not only safeguard the bloc’s neutrality but also reinforce its own standing as a credible regional leader.

Stay updated—follow Philippines Today on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for more stories.