As the Philippines commemorates the 164th birth anniversary of Dr. José Rizal this June 19, attention once again turns to the many facets of the national hero’s life—patriot, writer, martyr. But for architect Emmanuel Miñana, Rizal’s essence is captured not just in his novels or letters, but in the flourishes of ink that bore his name.

“Your signature is your autobiography,” Miñana once said.

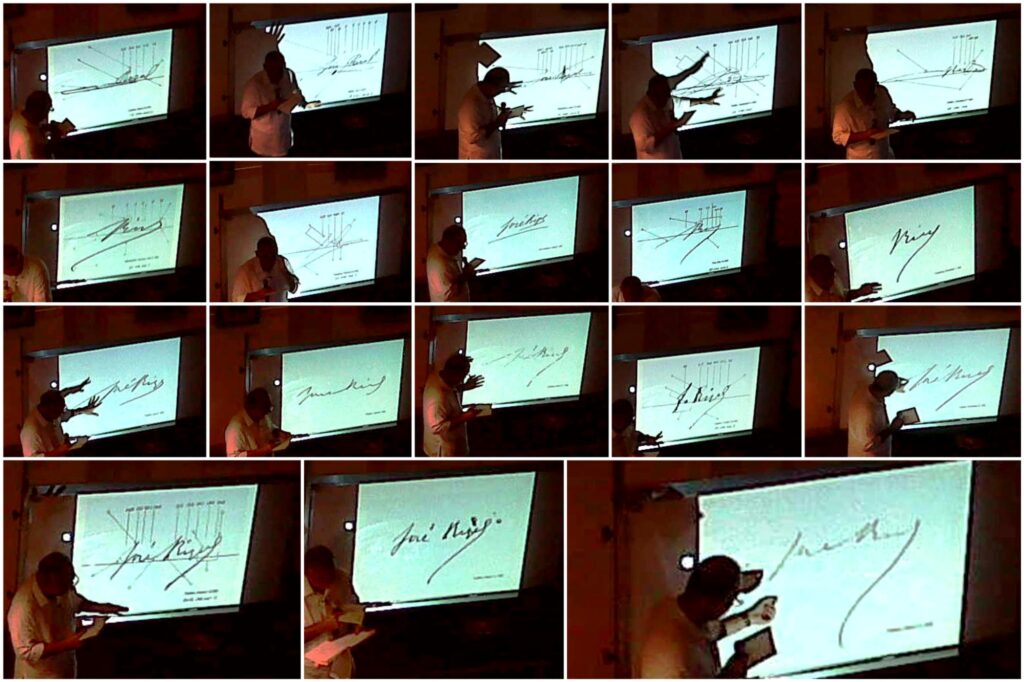

Fourteen years ago, on October 8, 2011, Miñana delivered a lecture titled “The Signature of José Rizal: A View From Within” at the Yuchengco Museum in Makati City. The event marked a personal milestone for the architect, who is also a practicing graphologist—a specialist in handwriting analysis. Through Rizal’s signatures, Miñana traced not just the evolution of a pen stroke, but the psychological journey of a man at once brilliant and burdened.

Graphology, though often met with skepticism, is the study of handwriting to discern personality traits, emotional states, and behavioral tendencies. A graphologist examines the slant, spacing, rhythm, and pressure of letters. Curves suggest emotion; angular forms, intellect or spirituality; and scribbles, a creative mind. Even subtle shifts can reflect dramatic turns in a person’s life.

“It’s normal for people’s signatures to change over time because the neurological impulses shift,” Miñana explained. “Impressions in the mind are transmitted to the hand.”

In Rizal’s case, Miñana charted these shifts across decades. He sourced samples from One Hundred Letters of José Rizal to His Parents, Brother, Sisters and Relatives, as well as the Lopez Museum and the Yuchengco Museum’s library, focusing particularly on Rizal’s correspondence with his close confidant, Ferdinand Blumentritt.

“I’m not a historian. I just have a fascination for people and, by the way, I read signatures,” Miñana told his audience in 2011. “When I started to read the letters to Blumentritt, I would look at Rizal’s signature and see how he was feeling when he was writing that… After seven hours in the library, I was in tears.”

From his youth as a prodigy to the final months before his execution in 1896, Rizal’s evolving signature revealed emotional peaks and personal fractures.

At 15, he used an exaggerated tail on the letter “l,” a flourish that reflected the self-conscious grandeur of intellectuals in Europe—Rizal’s peers included artist Félix Resurrección Hidalgo. Later, that same tail became sharp, brittle, even angry.

The sharpness of his “J” conveyed logic and spirituality. A looping “R” hinted at a tender, affectionate side, in contrast with the restraint often found in his prose. Miñana noted how certain letters lifted upward during Rizal’s years at the University of Santo Tomas—suggesting an inner struggle to rise above its conservative atmosphere.

In Europe, his pen freed itself. Signatures from that period flew across the page, the letters “S” and “L” soaring with the urgency of publication and purpose. But after the backlash to Noli Me Tangere, and pressure on his family from the friars, his downward strokes turned heavy with anger.

The signature traced heartbreak, too—his elation at meeting Josephine Bracken, the grief of losing their child, and the disillusionment with friends in Madrid. His signature to his mother turned cool and composed, words focused and stripped of warmth. The emotion instead bled into the way he signed his name.

“When somebody writes ‘My Dear ___,’ I can tell how dear that recipient is to the author,” Miñana noted.

One of the most telling moments came when Katipunan leader Pio Valenzuela visited Rizal in exile to ask him to inspire a revolution. Rizal’s letters suddenly enlarged—as though moved by fervor—but the long downstroke of his “l” plunged, as if anticipating a tragic end.

In the final letters to Bracken and his mother, Miñana saw not just a man preparing for death, but a person reconciling with the people who mattered most.

Now, in 2025, with nationalism continually reframed and Rizal’s life routinely canonized, Miñana’s approach reminds us of the man behind the monuments. His lecture, given 14 years ago, resonates anew—not as historical trivia but as a way to meet Rizal again, this time from within.

“The study of Rizal has been trite,” Miñana said back then. “I never came up close to his humanity where I could feel his struggles, the lack of faith in himself, his fight with depression… Beyond historical accounts of a polyglot and an intellectual, my signature analysis of Rizal reveals a human being who gifted the country with his life.”