One hundred years after Pope Pius XI introduced the Feast of Christ the King, the Catholic world is marking a centenary shaped by political upheaval, cultural tension, and a debate over the place of faith in public life.

Created in 1925 to assert a spiritual authority beyond any government or ideology, the feast still closes the liturgical year on the final Sunday before Advent. This year, it falls on November 23, underscoring its role as the Church’s year-end reminder that history ends not with a regime, but with a kingdom.

In the Philippines, the solemnity has become a quiet yet deeply significant observance for the country’s Catholic population. Parishes draw crowds for special Masses and novenas, while Eucharistic processions wind through streets, barangays, and parish courtyards.

Many communities conclude the day with benediction and the act of consecration to Christ the King, devotions that trace their roots directly to the feast’s founding document, Quas primas. Parishes named after Christ the King, including the well-known Greenmeadows parish in Quezon City, hold weeklong preparations that lead to large fiesta gatherings on the day itself.

Because the feast shifts each year, usually between November 20 and 26, it has become a natural bridge into the nation’s lengthy Christmas season. For Filipino Catholics, the celebration emphasizes a kingship rooted not in dominance but in truth, justice, love, and peace—values often highlighted in homilies and public prayers, especially in times of social tension or political division.

The centenary has also renewed attention to the reasons behind its establishment. In Quas primas, Pope Pius XI warned that efforts to “thrust Jesus Christ and his holy law” out of public life would deepen discord among nations. His concern reflected the environment of the 1920s: post-war disillusionment, the fall of monarchies, the rise of authoritarian movements, and the spread of secular ideologies that sought to confine religion to the private sphere. The feast, in many ways, became the Church’s answer to a world redefining power and authority.

Over the decades, the observance expanded beyond Catholicism. Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, and Presbyterian traditions adopted parallel celebrations, embedding the theme of Christ’s reign in their own liturgical calendars. In the Lutheran churches of Sweden and Finland, the day came to be known as “Judgment Sunday,” underscoring its association with the Last Judgment and Christ’s return.

The Catholic Church continued to refine the feast internally. Its first celebration in 1926 happened to fall on Halloween. In 1969, Saint Paul VI renamed it the “Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe,” and moved it to the last Sunday of the liturgical year, reinforcing its eschatological focus. Early Christian writers, such as Cyril of Alexandria, described this kingship as one “not seized by violence nor usurped,” but inherent to Christ’s divine nature.

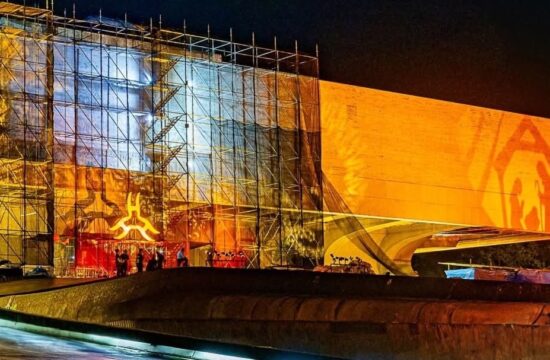

Today, the feast’s influence appears not only in worship but also in cultural and architectural landmarks. Among the most striking is the 33-meter Christ the King statue in Świebodzin, Poland—slightly taller than Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer. Another is Mexico’s Cristo Rey monument atop Cerro del Cubilete, a national pilgrimage site that commemorates the country’s struggle for religious freedom.

A hundred years on, the solemnity remains a global reminder that while nations rise and fall, the Christian narrative ends with a king whose reign believers see as enduring beyond them all. As millions prepare to mark the centennial on November 23, the celebration becomes less an echo of the past than a renewed affirmation of faith—one that continues to anchor communities and shape their vision of the world to come.

Follow PHILIPPINES TODAY on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for the latest updates.