Today, June 30, the country marks Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day, a commemoration of compassion, mutual respect, and an extraordinary chapter in shared history.

The law behind this annual event—Republic Act No. 9187, authored by the late senator Edgardo J. Angara—was inspired by a wartime episode that quietly transformed enmity into empathy: the Siege of Baler, a year-long standoff that ended not with bloodshed, but with grace.

Colonial Spain’s last stand

In 1898, as the Spanish Empire crumbled across its colonies, a small, forgotten garrison of soldiers in the coastal town of Baler, Aurora province, held fast—cut off from the world and unaware that Spain had already lost the Philippines.

Situated 140 miles northeast of Manila, with a rugged mountain range at its back and no harbor facing the Pacific, Baler was practically unreachable. According to the U.S. Naval Institute, the town’s remoteness made it the perfect setting for “an event that indelibly stamped the name ‘Baler’ in the annals of the Spanish Army.”

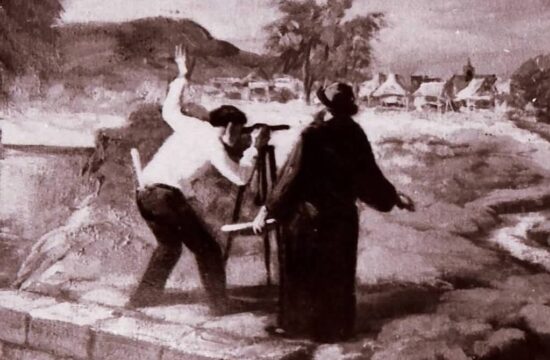

The Spanish Expeditionary Hunters Detachment No. 2, composed of three officers, 50 men, and a medical lieutenant, took refuge in the stone church of San Luis de Tolosa on June 27, 1898, upon noticing the town’s sudden desertion. They were soon besieged by Filipino revolutionaries.

For 337 days, the Spaniards held out against trench bombardments, food shortages, disease, and mental exhaustion. They refused repeated calls to surrender, even as dysentery and beriberi claimed their comrades—among them, Captain Enrique de las Morenas and Lieutenant Juan Alonso Zayas. Ammunition was scarce; red wine and tobacco were gone by August.

An attempted relief effort by the USS Yorktown failed in April 1899. A Filipino ruse involving a fake American flag was also dismissed by the suspicious garrison. Even when Spanish emissaries risked jungle trails and gunfire to deliver newspapers showing that Spain had ceded the Philippines to the U.S. months earlier, the soldiers doubted their authenticity.

Only on June 1, 1899, after Lieutenant Saturnino Martín Cerezo examined a bundle of Madrid newspapers confirming the loss of the empire, did he accept the truth. On June 2, the last 33 surviving Spaniards emerged from the church—exhausted, emaciated, and ready to face whatever fate awaited them.

Aguinaldo’s act of grace

What they encountered was not vengeance, but mercy. Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the First Philippine Republic, ordered that the Spanish survivors be treated with honor. His decree remains one of the most humane acts in wartime history: They are to be considered “not as prisoners of war, but as friends”.

Aguinaldo continued, commending the soldiers for “the valor, determination, and heroism with which that handful of men, cut off and without any hope of aid, defended their flag over the course of a year, realizing an epic so glorious and worthy of the legendary valor of El Cid and Pelayo.”

This rare show of compassion from a victor to the defeated became the moral cornerstone of Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day, formally established in 2002 and enacted into law in 2003. It is a day to remember not just conflict, but also reconciliation—an enduring lesson in dignity, humanity, and restraint.

Beneath the glory

While the siege is celebrated as an epic of honor, historian Jose Maria Cariño notes that it is also surrounded by silence, conflicting narratives, and unspoken tensions.

“There was a pact of silence, nobody uttered a word,” Cariño quoted Spanish journalist Manuel Leguineche, referring to the reluctance of both soldiers and clergy to discuss what truly happened inside the church. Most Filipino accounts were never formally written, and much of the local perspective was passed down orally.

The dominant version, Lt. Cerezo’s 1904 memoir El Sitio de Baler, became a bestseller and was even used as a siege survival manual by American military academies. However, it was written post-facto, likely with an eye toward glorifying the Spanish military and advancing Cerezo’s career. In contrast, Father Félix Minaya’s diaries, written during the siege, were never fully published. Franciscans later released excerpts, possibly omitting controversial details that could tarnish the church’s image.

Disagreements ran deep between the friars and the soldiers. Cerezo suspected the priests of siding with the Katipuneros and resented their presence in the church as “two additional useless mouths to feed.” The priests, who had prior knowledge of Spain’s defeat, tried to persuade the soldiers to surrender, but were dismissed as traitors. Ironically, Father Juan Lopez and Fr. Minaya remained in Baler a full year after the soldiers had returned to Spain and continued evangelical work for decades—leading Cariño to suggest that they, not the soldiers, were the true “Last of the Philippines” (Los Ultimos de Filipinas).

Even the suicide of Lieutenant Jose Mota is viewed differently. Fr. Minaya recorded it; Cerezo omitted it—possibly to avoid casting a shadow over the garrison’s image. Similarly, Dr. Rogelio Vigil de Quiñones, the medical lieutenant, often left the church to treat wounded Filipinos and townsfolk, actions seen by Cerezo as treasonous. Dr. Vigil, committed to the Hippocratic oath, simply said that what he did had nothing to do with loyalty to his country and that he did not believe in any ideology; he was only doing his job.

In one moment, Filipino troops even allowed their carabaos to wander into firing range so the starving Spaniards could eat. Cerezo described it as a “stroke of luck,” unaware—or perhaps unwilling to admit—that it was an act of quiet mercy. Another gesture came when Captain Antonio Santos of the Katipuneros allowed the Spaniards to pick oranges from the plaza without being shot at.

Reflecting later, when asked about Cerezo, Dr. Vigil offered a reserved but telling remark: “The lieutenant had to be harsh to maintain discipline. He was a good military man.”

A day to remember humanity

The story of Baler is not merely about war, honor, or defiance. It is about the choices people make when faced with desperation—and how compassion can emerge from conflict.

Today, both nations look back with mutual respect. In Madrid, a statue honoring the heroes of Baler stands near that of Jose Rizal. Documentaries like The Last of the Philippines: Return to Baler continue to explore this story’s many layers.

As the country marks Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day, the remembrance goes beyond soldiers and siege—it honors the mercy, memory, and shared humanity that emerged from conflict.