How ancient seafarers rewrote Southeast Asia’s human story

Long before recorded history, a small island in the Philippine archipelago was already buzzing with maritime innovation.

On the rugged shores of Mindoro, 35,000 years ago, early humans were not merely surviving—they were navigating open seas, forging tools from giant clamshells, and connecting with distant cultures across a vast oceanic frontier.

In an astonishing reappraisal of Southeast Asia’s ancient history, new research from the Mindoro Archaeology Project has unearthed one of the oldest and most technologically sophisticated maritime cultures in the region—perhaps the world. Spearheaded by Ateneo de Manila University in collaboration with global scholars, the study repositions the Philippines from a peripheral outpost to a central crossroads in the early human story.

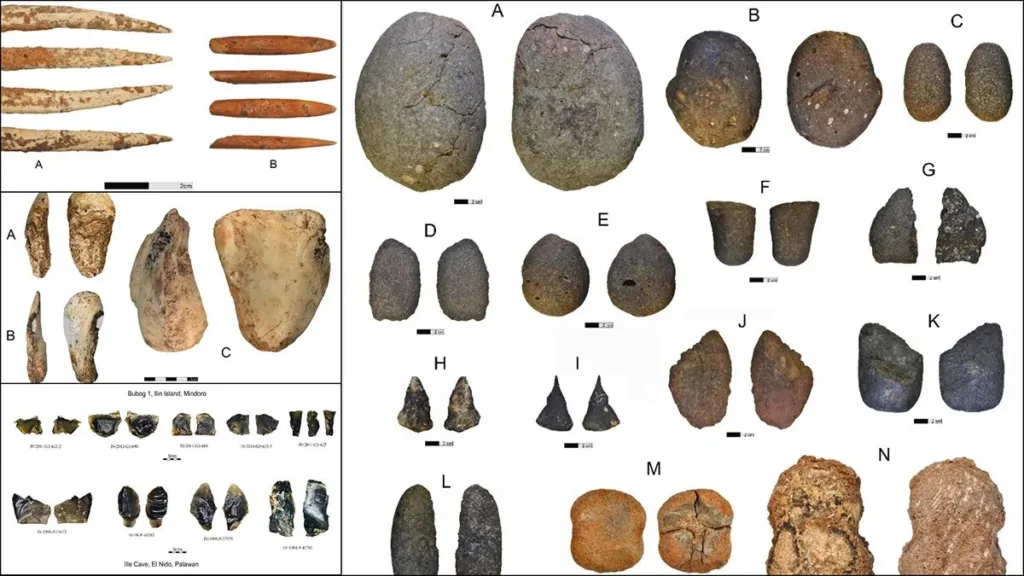

Published on June 1, 2025, the findings document evidence of Homo sapiens activity in Occidental Mindoro dating back over 35 millennia. Excavations on Ilin Island, as well as in the municipalities of San Jose and Magsaysay, revealed a surprisingly rich archaeological record: bone and shell tools, deep-sea fish remains, and burial sites that point to complex social structures.

But the real revelation lies in how they got there.

Islands that were never bridges

Unlike Palawan, which once formed part of an Ice Age landmass with Borneo, Mindoro and most of the Philippine islands were always separated by sea. There were no land bridges—only open water. Reaching them required intentional crossings and advanced maritime knowledge, suggesting that these early humans weren’t accidental castaways, but deliberate voyagers.

Their success in island-hopping across the archipelago marks a technological threshold: they possessed not only the physical tools but also the navigational and ecological intelligence to thrive in an insular world. It’s a capability more often associated with much later societies.

“Prehistoric migrations across ISEA (Island Southeast Asia) were not undertaken by mere passive sea drifters on flimsy bamboo rafts but by highly skilled navigators equipped with the knowledge and technology to travel vast distances and to remote islands over deep waters,” the researchers said in their paper.

Tools of the sea, signs of a network

Among the standout discoveries are adzes meticulously carved from giant clam shells (Tridacna), some dating back 9,000 years. These tools mirror others found thousands of kilometers away—from Borneo to Papua New Guinea—suggesting Mindoro was plugged into a maritime web stretching across Island Southeast Asia and into the Pacific.

Adding to this picture are fishing implements and faunal remains indicating the targeted capture of pelagic predators like sharks and bonito—evidence of an intimate knowledge of marine ecosystems.

“The remains of large predatory pelagic fish in these sites indicate the capacity for advanced seafaring and knowledge of the seasonality and migration routes of those fish species,” the researchers stated.

A burial beneath the stone

On Ilin Island, archaeologists unearthed a 5,000-year-old grave: the skeletal remains of a human curled in a fetal position, cradled by limestone slabs. This flexed burial echoes funerary practices from across Southeast Asia and hints at shared belief systems or social rituals spanning islands and even continents.

Far from isolated, these early islanders were part of something larger—a cultural and technological exchange that pulsed across the sea long before modern borders took shape.

Rethinking prehistory

The Mindoro findings challenge long-held assumptions that early Southeast Asians were confined to coastal foraging or sporadic migration. Instead, they paint a picture of determined exploration, ecological mastery, and cultural complexity.

By tracking nearly 40,000 years of continuous human adaptation, the Mindoro Archaeology Project is transforming how scientists view migration not as a linear push from Africa to Eurasia, but as a mosaic of maritime journeys, many of which began—or converged—on islands like Mindoro.

0 Comment