‘Makibaka’: Filipino American art frontlines New York’s 400th anniversary

New York City marks its 400th anniversary this year—a time not only for celebration but for reflection on the stories that shaped it. Across the boroughs, commemorations honor both iconic milestones and the lives of communities too often left out of official histories.

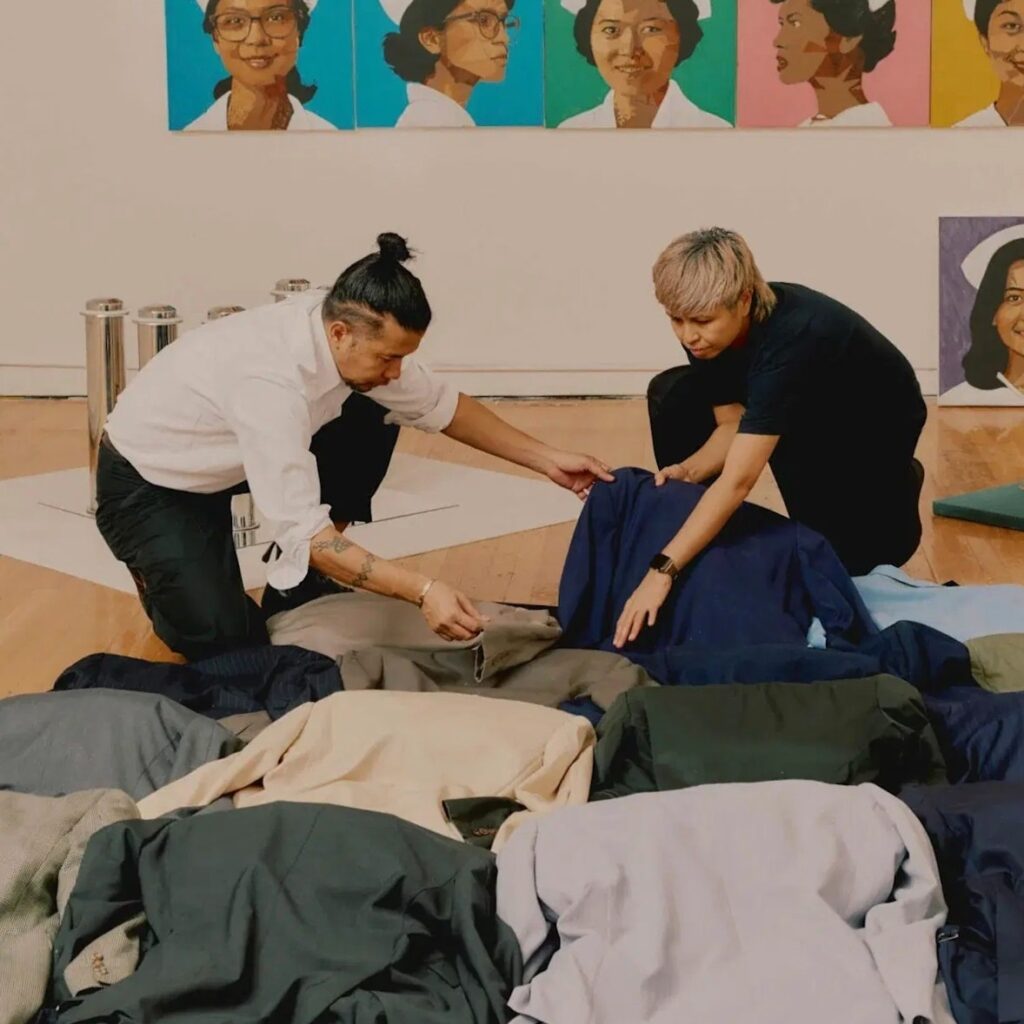

Among the most striking of these is at the Queens Museum, where the Filipino American art duo Abang-guard—Maureen Catbagan and Jevijoe Vitug—present Makibaka (Tagalog for “coming together”), a vivid meditation on immigration, labor, and solidarity.

The duo’s name itself signals their layered approach. A play on avant-garde and their shared past as security guards at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, Abang-guard reclaims the idea of guarding—both as labor and as artistic front line.

“The term ‘avant-garde,’ it’s a front liner. It makes sense that we’re museum guards but also artists,” Catbagan explained in an interview with the Queens Museum. “We’re guarding something of value. Our experience in the back informed our practice, and now we’re in the game.”

Their exhibition builds on a yearlong residency responding to the 1964–65 World’s Fair, specifically the Philippine and New York State pavilions. Vitug revisits the paintings once considered cutting-edge—Warhol, Rosenquist, Lichtenstein—recasting them to center Asian American narratives.

“At that time, these pieces were considered avant-garde,” Vitug said in the Queens Museum interview. “I wanted to make versions of the works; but instead of being about American consumerism, they are about the narrative of Asian Americans, specifically Filipino nurses and migrant labor.”

Catbagan added, “[Vitug] takes the American modernist and inputs Filipino subjectivity into the paintings. Even though there was a Philippines Pavilion, the depiction of the history was more like a colonial narrative.”

That sense of omission drives much of Makibaka. Catbagan and Vitug not only reconstruct the Philippine Pavilion’s salakot-shaped roof but also install time capsules that layer past, present, and future. Inspired by the Westinghouse capsule of 1965, theirs hold symbolic gifts for the labor movement—tributes to farmworkers and nurses who carried Filipino history into the American fabric.

“Our gifts commemorate the Delano Grape Strike, which occurred on September 8, 1965,” Catbagan explained. “The strike was the largest solidarity movement between Mexicans and Filipinos. They created the working conditions we have now, all these things we take for granted. But they were hard-won with solidarity movements, a lot of blood, sweat, and tears.”

Fieldwork was central to the residency. The artists traveled to California to speak with descendants of the farmworkers who led the strike. “We drove to Delano,” Vitug recalled. “It’s different between when you read about it and when you dare to absorb the heat, smell the pesticide.”

Catbagan added, “To acknowledge that in a public place, to give permission to others to put their origin story on the table, is an amazing thing.” That process of listening, researching, and translating into art exemplifies their commitment to solidarity as lived practice.

Among the exhibition’s centerpiece works is America’s Most Help Wanted (after Warhol), Vitug’s homage to Filipino nurses whose migration was shaped by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Using photographs sourced from friends and community members, he reimagined Andy Warhol’s censored mural Thirteen Most Wanted Men not as criminal portraits but as tributes to care workers. The result is both personal—one painting draws on a photo of a nurse in Minnesota—and political, repositioning immigrant labor at the center of American modernity.

For Catbagan, the message is simple but urgent: “Being an American is intrinsically an immigrant story. Immigrants built this nation together—which is makibaka, a solidarity—and that identity should not be put in the background.”

That perspective resonates in this anniversary year. Founded as a Dutch trading post in 1625, New York quickly became a polyglot colony of Europeans, Africans, and the Indigenous Lenape before transforming into the metropolis it is today. Its story was never only about power or commerce; it has always been about the countless lives—farmers, nurses, laborers, immigrants—who sustained it.

In Makibaka, Abang-guard places those stories where they belong: at the very heart of New York’s four centuries. Abang-guard: Makibaka runs at the Queens Museum through October 5, 2025.

0 Comment