On a humid September morning in 1984, as the Philippines edged toward political collapse, a shimmering brass bell rang in Malacañang Palace—meant, its foreign keepers said, to make an entire nation “invincible.”

The moment now lands like a surreal footnote in Philippine history: a late-strongman spectacle in which Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s followers descended on Manila with promises of “perfect civilization,” and then-President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Sr.—embroiled in crisis—embraced their mysticism with the zeal of a man grasping for a new source of legitimacy.

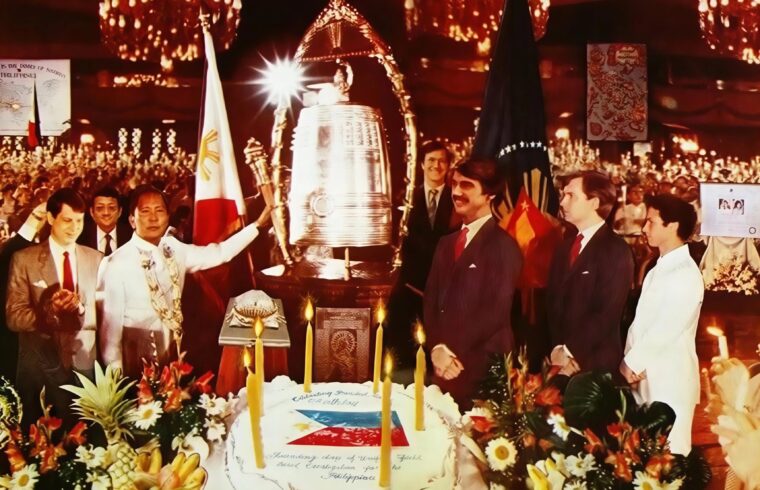

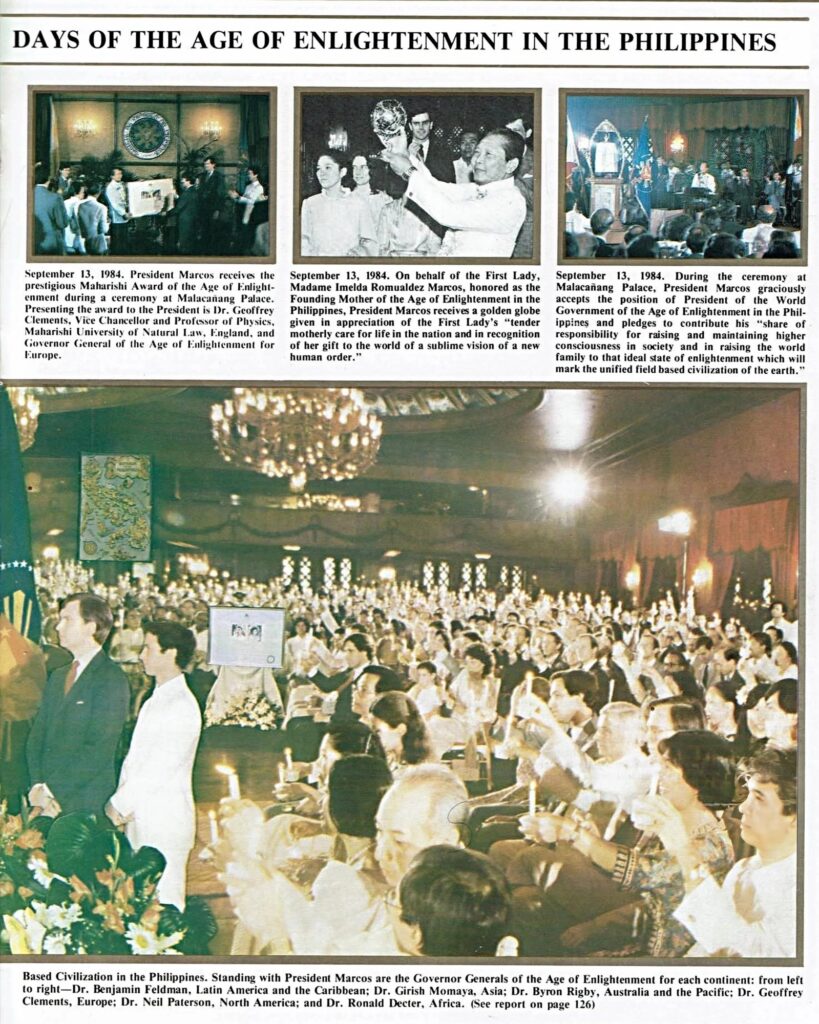

The Washington Post’s William Branigin reported that Marcos and his wife, First Lady Imelda Romualdez-Marcos, were proclaimed the “founding father” and “founding mother” of the Maharishi movement’s so-called “age of enlightenment,” a title bestowed amid birthday fanfare, golden torches, and chants of spiritual triumph on September 11–13, 1984.

The movement even presented Marcos with the “Maharishi Bell of Invincibility,” whose inscription declared that “invincibility [was] rising in the nation under the leadership of President Marcos,” a flourish that read like propaganda disguised as metaphysics.

Yet the mass arrival of roughly 1,200 largely Western adherents—who had leased entire hotels, including presidential suites costing nearly $3,000 a night (during that time)—wasn’t just a curious foreign visitation.

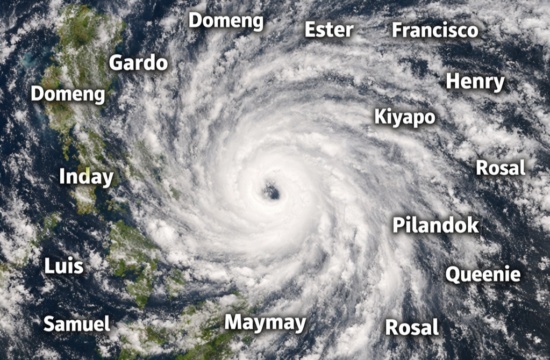

Branigin reported that the group launched a blitz of newspaper advertisements urging Filipinos to “adore” Marcos in his elevated spiritual role and asserting that their “Maharishi Technology of the Unified Field” could reverse aging, avert typhoons, and create a “problem-free life.” Students, they claimed, could even stabilize the atmosphere by meditating 10 to 15 minutes a day. It was mysticism marketed as national salvation, wrapped in the political choreography of a regime struggling against an emboldened opposition after the assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr.

The centerpiece of the Maharishi campaign—its pivot from spectacle to confrontation—was the sudden acquisition of the University of the East on September 28, 1984. It was the country’s largest private university, with roughly 47,000 students, and its takeover by the Age of Enlightenment Foundation of the Philippines, a local affiliate of the group, sparked immediate outcry.

Branigin wrote that the group planned to introduce what it called the “Maharishi Unified Field Based Integrated System of Education,” leaning on esoteric explanations involving “supersymmetric binding force of the gluons.” Students read that as a euphemism for an ideological intrusion. The university’s student government body condemned the purchase as “direct intervention,” arguing it would weaken anti-government activism on campus.

Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin, the most influential voice in the Catholic hierarchy and a persistent Marcos critic during the ’80s, denounced the Maharishi group as a “dangerous cult”. He convened a meeting of scholars and clergy to craft a national response, while the Securities and Exchange Commission and Ministry of Education opened investigations into the legality of the foreign-funded purchase. Even establishment figures aligned with the regime, like Batasang Pambansa member Helena Benitez, called for further scrutiny after learning there were plans to acquire up to eight more schools.

Outside the official arenas, Manila’s streets carried the real verdict. Students marched, boycotted classes, and scrawled slogans linking the movement to what they called the “U.S.–Marcos dictatorship.” To them, the influx of meditating foreigners—armed with hotel keycards, spiritual titles, and a political halo from the Palace—felt less like enlightenment and more like an incursion dressed in robes.

Viewed from the present, the episode resembles a strange rehearsal for contemporary political theatrics, where spectacle often masquerades as substance and power seeks refuge in symbolic gestures. The Marcos Sr. regime’s willingness to elevate a foreign spiritual movement, in exchange for celestial legitimacy, mirrors today’s entanglement of politics with curated mythologies and influencer-style messaging: leaders announcing prophetic visions, movements promising national rebirth, and audiences sorting truth from performance in real time.

Back in 1984, the Maharishi followers declared the Philippines the new “spiritual center of the world.” But as the bell sounded in Malacañang, it was the clamor outside—students, activists, citizens demanding accountability—that foretold the real future. The so-called “Unified Field Based Civilization” dissolved almost as quickly as it appeared; the dictatorship fell less than two years later.

History rarely offers parallels so stark they feel choreographed: a nation once promised “invincibility” by a faltering strongman now governed by his son, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., navigating new storms of disinformation, economic strain, and geopolitical tension.

The 1984 spectacle of borrowed mysticism reads today like an ancestor of the political stagecraft that shapes modern politics—grand narratives promising reforms and accountability while critics warn of eroded institutions and recycled dynastic power. And so the picture Branigin captured endures: Marcos Sr. ringing a bell to summon “invincibility,” while decades later his son navigates a landscape where those echoes grow sharper, and the nation listens closely for what comes next.

Follow PHILIPPINES TODAY on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe on YouTube for the latest updates.