For once, the tax system favors the many over the few. The flat 20% levy on interest income, introduced under the Capital Market Efficiency Promotion Act (CMEPA), doesn’t punish savers—it puts an end to years of built-in advantages that let the wealthy lock away capital and enjoy lower tax rates.

Contrary to the social media frenzy framing this as a “new tax,” it’s nothing of the sort. The levy has existed since 1998, embedded in the tax reform law under Republic Act No. 8424. What is new, however, is the removal of preferential rates previously afforded to long-term depositors—largely the affluent—under the recently passed measure.

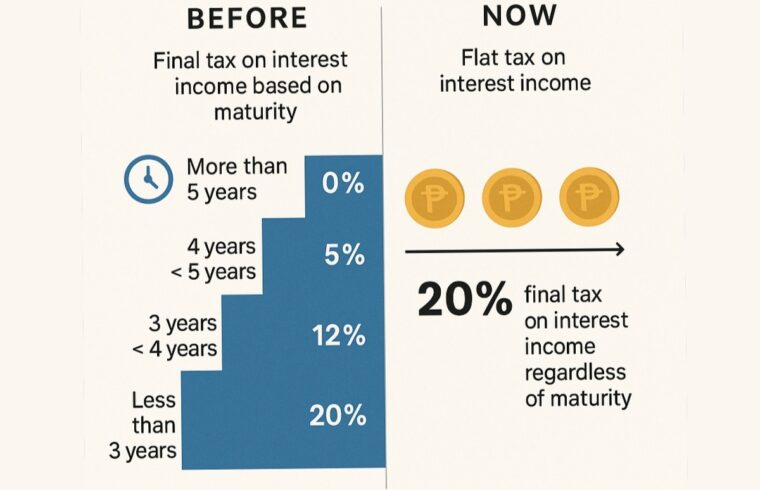

For decades, the tax framework quietly served as a reward system for the wealthy. Interest income from peso bank deposits was taxed on a sliding scale based on the maturity period: funds held for over five years? Tax-free. Four to five years? Just 5%. Three to four years? 12%. Anything below three years? The full 20%.

This structure was originally designed to encourage long-term savings and capital stability. But in practice, it disproportionately benefited individuals who could afford to lock away their money for half a decade or more—essentially those who needed the tax breaks the least.

The Department of Finance (DOF), in its explanatory memo, asserts that CMEPA merely “levels the playing field.” They’re right. The reform equalizes the tax burden across all types of savers by instituting a uniform 20% final tax on all interest income, regardless of the account’s maturity. In short: no more loopholes, no more legacy privileges.

But therein lies the rub.

A flat tax rate, while ostensibly equitable, can still feel regressive in application. For low- to middle-income earners, whose bank deposits function more as a budgeting tool than an investment strategy, the interest earned—already meager—now feels doubly diminished. The average Filipino savings account yields around 0.25% to 1% per annum. Taxing that interest at 20% turns what was already a microscopic gain into a symbolic gesture at best, a deterrent at worst.

From a behavioral standpoint, this could discourage small savers—especially those willing to keep their money in the bank longer—from doing so at all. Instead, they may turn to informal saving schemes or immediate spending, ironically undermining the culture of long-term saving that the original tiered tax system was meant to encourage.

Meanwhile, high-net-worth individuals, who have broader access to lower-taxed financial instruments such as government bonds or offshore accounts, will likely remain insulated from this recalibration.

This is not to say that CMEPA is bad policy. It’s a step toward removing tax arbitrage that unfairly favored those with wealth and time. But like many well-intentioned reforms, it stops short of delivering full equity.

Though the law is now in place, there’s still room to refine how it’s applied—through clearer rules or future adjustments that protect small savers. A basic exemption for interest earnings below a certain amount, for instance, could help preserve fairness without reintroducing unnecessary complexity.

The government stands to benefit from simpler rules and broader compliance. But without safeguards for vulnerable depositors, it risks alienating the very people it hopes to draw into the formal financial system.

Bank savings should not be viewed as a luxury, but as a fundamental instrument of household resilience. In a country where over 60% of adults remain unbanked, taxing modest interest income might be legal—but it sends the wrong message.

At its core, the discussion isn’t about whether interest should be taxed. It’s about who should bear the burden and how to balance revenue goals with inclusive growth. There is still room for nuance—and a chance for lawmakers to prove this isn’t just another blunt instrument disguised as reform.